Description

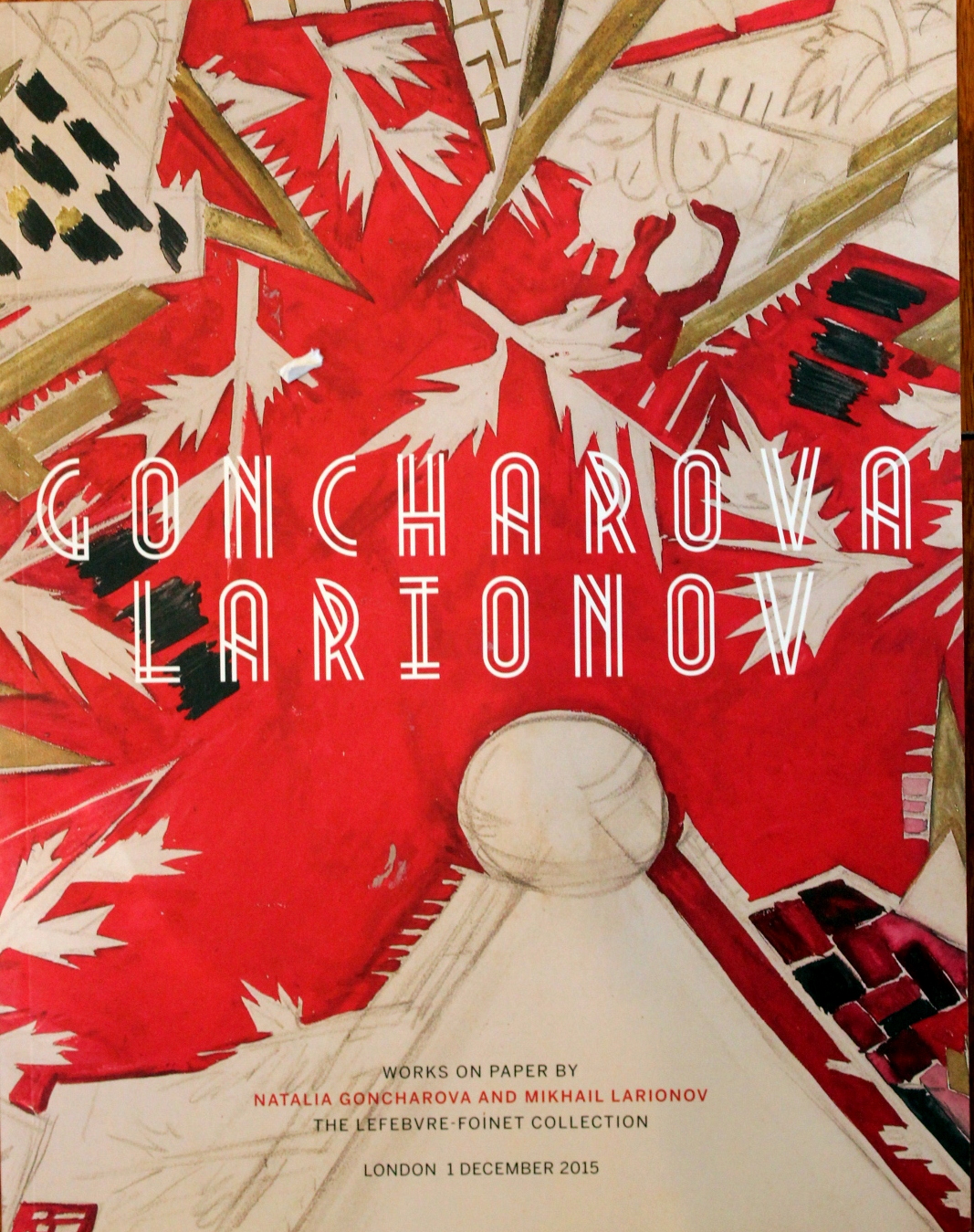

WORKS ON PAPER BY

NATALIA GONCHAROVA AND MIKHAIL LARIONOV

THE LEFEBVRE - FOINET COLLECTION

12/1/15

LONDON

120 lots

The Integrated Art of Natalia Goncharova and Mikhail Larionov:

Design, Drawing, Ornament in the Lucien Lefebvre-Foinet Collection

e oeuvres of Natalia Goncharova and Mikhail Larionov still challenge scholars devoted to the many creative enterprises in which both artists engaged over the course of their long careers. 1 Even the most easily documented aspect of their professional lives and one that brings them closest to their European cohort – their dependence on particular collectors and patrons – has limited our understanding of their work. Paintings that were intended as elements of multipart compositions reside in collections in Paris and Moscow, London and Los Angeles. 2 Theatrical designs, always a collective endeavour and a total dramatic-ornamental experience, have been dispersed to multiple public and private collections through gift and purchase. As modernist artists trained in the techniques of academic painting who rejected that culture, they managed to develop over the course of their long lives mastery in all manner of visual arts disciplines: set and costume design, clothing as well as textile design and manufacture.

L15115_Goncharova_1

GONCHAROVA AND LARIONOV IN THE WORKSHOP OF THE BOLSHOI THEATRE WORKING ON PREPARATIONS

FOR LE COQ D’OR, 1913-1914, ARCHIVE OF THE STATE TRETYAKOV GALLERY

Yet the appeal to the historian of the present collection lies precisely in this paradox: it contains its traces of the dispersal of projects to collections around the world, and traces of their as yet unreconstructed, deliberate methods of working across diverse media. The Lefebvre-Foinet Collection reveals vital elements of a career (primarily Goncharova’s), that spanned neo-impressionist pastels (lot 290), studies for primitivist paintings and evidence of her constant commitment to the decorative arts which dominated both artists’ working lives following their emigration from wartime Russia. The works by Larionov that form a small part of the collection include his characteristic sketches, caricatures, and studies of dancers that have long served as primary records of company life within Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes.

Among Goncharova’s studies for recognizable paintings are the Head of a Peasant (lot 258), which may have been created in preparation for Peasants Gathering Grapes (1913), in the State Art Museum of Bashkortostan, Ufa. Of her later Parisian paintings, in addition to numerous studies of Spanish dancers, at least one major study (a cartoon) for the fresco planned for Mary Hoyt Wiborg’s villa, demonstrates her talent for imagining projects, and physically transferring them, from one scale and medium to another. This is possibly the image with which Marina Tsvetaeva begins her long study of Goncharova’s oeuvre, in 1929, as a lament (lot 266).3 A more finished drawing is now in the Tretyakov Gallery collection in Moscow.

L15115_fashion

The insight provided by the Lefebvre-Foinet collection into Goncharova’s working methods as an artist and designer is extraordinary. Numerous sketches in a variety of media, pencil, charcoal, gouache belie the claim that she worked spontaneously on her oil paintings. While this may be true for some compositions, the Lefebvre-Foinet collection proves conclusively that, as Alexander Benois claimed in 1913, she was a master of the small, expressive study.4

Sketches that may have served some projective, design purpose, especially the studies for the Parisian fashion house Myrbor, are realised as gestural masterworks in themselves. Indeed, among the highlights of the collection are a series of large figure drawings. In view of their large scale and delicate condition, one wonders if they were made for a clothing manufacturer. (For what purpose, then – the invention of more detail, or for display in signage or advertising?) They may also have served another expressive purpose, revealing as they do, Goncharova’s acerbic humour and incisive critical social perspective on the bourgeois world of fashion and entertainment she now inhabited, following years of struggle entering the nascent Russian market for new art.5 This series comprises a Spanish male figure (lot 203), flamenco dancers (lots 204-206) and an extravagantly dressed cocotte (lot 249). All three record Goncharova’s nuanced attention to decorative detail while registering her fascination with the new cultures to which she was exposed, especially in Spain. The series was based to some degree on life-study, a first step within her working process, no matter what the final function of the image might be – whether for stage or commercial design use. Correspondence transferred to the Tretyakov Gallery archives in Moscow from the artists’ Paris studio documents the systematic way in which she moved from sketch to formal study, especially during her trip to Spain with Diaghilev’s company. 6 The visual evidence is in this collection.

L15115_Spain

Similarly, the sketches for Bogatyrs may be distinguished from her detailed, informative images for other ballet projects. In a rapidly executed series of figure studies, she diminishes her focus on descriptive detail. Still, the sketches register the expressive acumen and design insight she had acquired over years of study of the popular arts, and literature (byliny, or heroic epics) (lots 223 and 225). In a rare display of kinetic potential, they also record the energy of action envisioned by the dance.

A classical rigour in graphic techniques consistently informs Goncharova’s art; her mastery is evident even at the material level of design, particularly in applied ornament. An extraordinary series of sketches for fabric magnify elements of Central Asian (lot 224) and Slavic ornamental design into dynamic expressive figures. Goncharova repeats shapes through her use of contour line while varying colour contrasts (lots 244 to 246). These drawings may have been created in preparation for patterns on tracing paper that would be used to construct individual items, as they are realised on a different scale than most of the other works in the collection. Goncharova did not dedicate her creative talent to mass-production.

Instead, she turned her production skills to the actual materials employed in her work as a designer. Particularly remarkable are the meticulous, tight, decorative patterns that distinguish her textile and dress design from her painterly work.

Here we see the implicit planning and expressive intention embodied in Goncharova’s art in all media. Her studies for clothing and textile patterns are outlined in pencil, and then painted in gouache without accompanying swatches, or colour tests. Set and costume designs exist in various states, with different stages realised in distinct media. Two large pattern designs on tracing paper give detailed instructions for embroidery on a coat created for Myrbor (lot 243). Typically, drawings in the Lefebvre-Foinet collection amplify a pattern’s visual effect while also revealing the level of Goncharova’s engagement in the design process, both of which are less evident in the finished sketch of the coat itself (located in the Tretyakov Gallery).

L15115_design

Several series of works dispersed in various collections link the processes required for producing a range of disparate but related projects. Extremely rare is an as yet unidentified set design, in model form (lot 260); a similar, though earlier, maquette for Sonneur is located in the collection of the Musée national d’art moderne (Centre Georges Pompidou).7 The collection also contains actual tracing paper figures of puppets created for Karagöz, for Julie Sazonova’s Parisian marionette theatre (lot 274). Based on Turkish examples that Sazonova had brought back from Istanbul, Goncharova’s designs are still clearly her own. These figures reappear in the orientalist scenes she created for the programme for the same production (lots 271 to 273, 275 and 276). Similar parchment paper cut outs, also from the artist’s studio, are located in the Tretyakov Gallery. The same images were later mass-produced in print format.8

A similar range of works document the process of creating and imagining different uses for her set designs. Sketches for Diaghilev’s Spanish themed balletsTriana and Espagne produced in 1916 were unrealised as actual sets, but the designs themselves may have been reexecuted for exhibition display (lots 201 and 207). These works visualize the bridge she perceived between popular cultures, Spanish and Russian, in brilliant graphic ornamental detail. Goncharova wrote frequently about her powerful attraction to Spanish culture, to her friend the poet Sergei Bobrov in Moscow, and in other, more historical, musings on her creative path.

Other highlights of set design represented in the collection are those for the unrealised ballets Liturgie (1915), and Les Noces (1915-23). The versions of costumes for the first document the process of experimental reuse of imagery that characterized much of Goncharova’s oeuvre, both before and after emigration. Tracing paper variations of the St Mark figure show the process whereby she transformed a drawing into a pochoir print; the drawing of the Seraphim exists in its post-tracing process state, with pencil covering both sides of the paper (lots 215 and 216). A stunning, large sketch on tracing paper represents the first stage of the curtain design (lot 214) for a collage that has been reproduced many times, and resides in the Metropolitan Museum’s collection, in New York City. By contrast, a more complete series of drawings and watercolours document the process of designing The Fair at Sorochyntsi (1926-40) and Cinderella (1938).

Most rare, are the series of set designs for the scenes she anticipated would emerge from Igor Stravinsky’s decade long work on Les Noces (lots 208-210). These large sketches on tracing paper are the last in a sequence of planned sets whose visual force depended on the expressive power of ornament. Probably dating from 1917-20, and sometimes designated the ‘North-Russian’ version owing to the muted blue and rose colour palette that she described in her memoirs, these images (although not coloured) are more subtle and historically specific than the earlier versions.9 When Goncharova began the project in 1915, she drew heavily on the fantastical merging of colour and nearly geometric form that had made Le Coq d’Or the event of the 1914 Parisian theatre season.

As this essay goes to press an exhibition of Sonia Delaunay’s paintings, design, and material artifacts connected to the creation of both, has recently come to an end at London’s Tate Modern. In the first decades of the twentieth century, no one in Moscow, St Petersburg, or Paris could have imagined that a retrospective of the creative oeuvre of one Russian woman artist (Sonia Delaunay) would overshadow one dedicated to the work of an even greater talent (Natalia Goncharova). In view of her international prominence in the early part of the 20th century, it is astonishing that, Goncharova’s recent retrospective held at the Tretyakov Gallery in 2013-14 remained a Moscow affair. The present display of works collected by the multigenerational art suppliers, especially Lucien Lefebvre-Foinet, in Paris, compensates somewhat for this gap, and shows us why it should matter.